Laapataa Lady: The world has gone bonkers over the ‘missing’ Kate Middleton

In a post AI world, rarely have images mattered as much as they do now. An innocuous-enough photograph of a mother and her three children has created a stir that is bouncing off our planet as if the first bugle of armageddon has been sounded. The picture that launched a thousand conspiracies Kate Middleton, on track to be the future queen of England, released a picture on Mother’s Day presumably with the intention to scotch rumours about her ‘disappearance’ from public view since Christmas last year. On January 17, official sources had informed the British public that she had undergone…

Missing women in search of themselves

In Kiran Rao’s new film, Laapataa Ladies, the brides are making their own journeys, gradually spreading their wings and discovering parts of themselves they have never known The brides, veiled and dressed nearly identically in red, have been swapped. And what seems to be the starting premise of a wholesome comedy is actually a portrait of women in search of themselves. The first word of the title Laapataa Ladies translates both as lost and missing, the word chosen by Amartya Sen to talk about women and girls who were aborted before they could be born. Laapataa Ladies (Jio Studios and Kindling Pictures)…

India, we have a rape problem. What are we doing about it?

Remembering the life and work of Minnette da Silva

Sri Lanka’s first woman architect is , sadly, largely forgotten Truth be told I had not heard of Minnette de Silva. Goeffrey Bawa, Sri Lanka’s lionised and feted architect, yes. His influence can be seen in not just his own former country estate in Lunuganga but in buildings such as the new Parliament house. But Minnette who? On a visit to the island nation that gave the world meaning to the word serendipity, I stumbled upon a solo show at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. It was, unusually, of a housing project that had been designed by Sri Lanka’s…

We, the elite of India, are to blame for the state of our cities

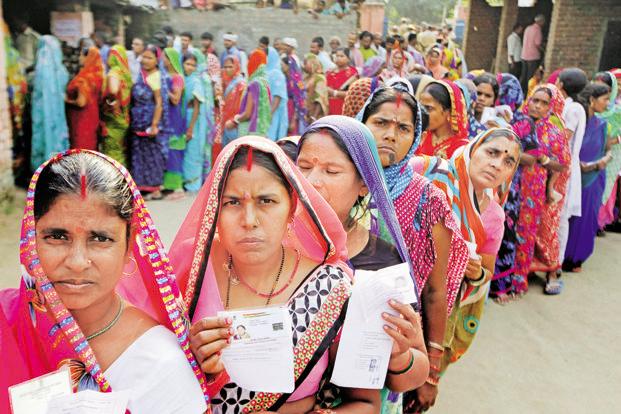

Are some women in India more unequal than others?

How do you continue to hold out hope with the weight of the State’s boot on your neck? The message is clear: In their quest for justice, women are unequal citizens, some more unequal than others. The men were garlanded and feted at the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) office in an utterly obscene display of triumphalism that mocks every woman who seeks justice for rape. (PTI) Eleven men were sentenced to life imprisonment for the gang rape and murder of 14 people in the 2002 Gujarat riots. Among their victims was Bilkis Bano, 19 years old and five months pregnant. She…

Are some women in India more unequal than others

How do you continue to hold out hope with the weight of the State’s boot on your neck? The message is clear: In their quest for justice, women are unequal citizens, some more unequal than others. The men were garlanded and feted at the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) office in an utterly obscene display of triumphalism that mocks every woman who seeks justice for rape. (PTI) Eleven men were sentenced to life imprisonment for the gang rape and murder of 14 people in the 2002 Gujarat riots. Among their victims was Bilkis Bano, 19 years old and five months pregnant. She…

Dear ladies, your ambition is showing (gasp)

She puts her career before her only child. “I’m sorry kid. I really want to come. But something’s come up at work.” The disappointed 10-year-old shoots back: “You’re working every day. You don’t like to do anything else.” That’s the script for when Jagruti Phatak, single mom and investigative journalist, tells her son she can’t take him for the movie they had planned to watch. The TV series is Scoop on Netflix and it is based on the true story of crime reporter Jigna Vora. Jagruti’s ambitions are pretty straightforward and include (though not necessarily in this order): To become…

Busting the myth of the “superwoman”

You’ve heard the story. That amazing woman who has it all, does it all – and always with a smile. Kids homework. Check. Taking mom for her doctor’s appointment. Check. Employee of the month. Check. Home-cooked nutritious meals. Check. Partner’s go-to shoulder to lean on. Check. Mentor to younger women at work. Check, check, check.

An increasing number of women don’t want kids. They shouldn’t have to face a backlash for what’s a personal decision

Picture credits: @yolandayoungesq/ The Guardian Early in February, Sidra Aziz tweeted: “I am 31 years old and over the last few years I have very consciously chosen not to have children ever. Marriage, maybe. Children, no.” It was an innocuous enough tweet but the 31-year-old data product manager was taken aback by the response. Within hours, it had generated 42,330 impressions and over 500 replies. The kinder ones advised her to have “one kid at least” for “positive energy”. Others called her a child-hater and still others warned that she would die alone with nobody to bury her. “Nearly all…

Marital rape: Ball’s in the court

India is one of 36 countries where it is not a crime to rape your wife. Well, if your wife is younger than 15, then even the law says intercourse with her is rape. But that is the only exception. Now, even this exception is under judicial scrutiny as a two-judge bench of Justices C Hari Shankar and Rajiv Shakdher of the Delhi High Court begins hearing from two individuals and two NGOs, RIT and the All India Democratic Women’s Association. It is also hearing from an amicus curie, or friend of the court, Rajshekhar Rao and has asked another…

A home-maker’s worth: Madras high court puts a value

A still from The Great Indian Kitchen The cash really began rolling in after 1983 when Kannaian Naidu got a job in Saudi Arabia. His wife, Kamsala would be staying back with their three children in Neyveli, Tamil Nadu. As a single-parent, she had her work cut out and Kannaian assured her he would send money back home. It was a tidy sum. Between 1983 and 1994, Kannaian was able to send back enough for Kamsala to buy four properties. Each time he’d come to visit, he would bring cash, gold and jewellery. By the time he returned for good…